Accessibility

Accessibility is a design feature of organisational or social structures that facilitate or impede people's access to resources (information, education, participation, health care, labour market, housing, infrastructure, etc.) or services (here especially administrative services) (Stauber & Parreira do Amaral 2015). Ensuring this access is a central task of municipal administrations.

Digital information and communication channels are suitable for simplifying access, e.g. to administrative services. Impediments to accessibility are discussed under the term "digital divide". Infrastructural factors ((broadband) network access, hardware) are located on a first level (first level digital divide). Individual skills, knowledge or resources (media competence, social status, etc.) are factors of the second level (second level digital divide) (Kersting 2020; Norris 2001; van Dijk 2006). Politics, administration and society have the task of ensuring accessibility for all stakeholders in the (further) development, implementation and use of digital structures and processes.

References:

Kersting, N. (2020). Digitale Ungleichheiten und digitale Spaltung. In T. Klenk, F. Nullmeier, & G. Wewer (Hrsg.), Handbuch Digitalisierung in Staat und Verwaltung. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, S.219-229 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-23668-7_19

Norris, P. (2001). Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide (1. Aufl.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139164887

Stauber, B., & Parreira do Amaral, M. (2015). Access to and Accessibility of Education: An Analytic and Conceptual Approach to a Multidimensional Issue. European Education, 47(1), S.11–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2015.1001254

van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2006). Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics, 34(4–5), S.221–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2006.05.004

Agency

Agency refers to the ability of personal and social actors to act in a way that enables them to achieve desired goals against the background of available resources and opportunity structures. The strategies of action developed in this process usually represent implicit, general models of action, into which both routines of action, creative moments and practical-evaluative aspects of action are integrated. In relation to individuals, experiences of effectiveness play a significant role; in relation to social actors such as social organisations or administrative units, agencies are reflected in the instrumental arrangements with which their goals are to be implemented. Agencies therefore also play a decisive role in determining capabilities. They make it possible for opportunities to be realised.

References

Grundmann, M. (2010). Handlungsbefähigung – eine sozialisationstheoretische Perspektive. In: Otto, H.-U., Ziegler, H. (Hrsg.), Capabilities – Handlungsbefähigung und Verwirklichungschancen in der Erziehungswissenschaft. Wiesbaden: VS, S.131-142

Grundmann, M. (2020). Agency. In: Bollweg, P.; Buchna, J., Coelen, Th., Otto, H.-U. (Hrsg.), Handbuch Ganztagsbildung, Band 2, 2. Auflage: Opladen: Springer VS, S.1707–1718.

Capabilities

The capability approach has developed from welfare-economic and justice-theoretical considerations by A. Sen and M. Nussbaum. It serves to analyse individual and social realisation potentials, which arise as a dynamic result of the joint action of individuals in the context of structural and thus socio-cultural frameworks (here, e.g. an urban milieu). The complex interaction of different levels of action, which are prerequisites for individual quality of life, is taken into account within the framework of current concepts of the capabilities approach in principle and in an increasingly differentiated manner (see, e.g., Gasper 2002). Central to the (ultimately also empirically founded) understanding of such structures appears to be the unifying concept of transformation factors, which Robeyns describes as a multidimensional construct of personal, environmental and social factors (Robeyns 2005: 99).

References

Grundmann, M., Steinhoff, A. & Edelstein, W. (2011). Social Class, Socialization and Capabilities in a Modern Welfare State: Results from the Iceland Longitudinal Study. In: Leßmann, O., Otto, H.-U., Ziegler, H. (Hrsg.), Closing the capabilities gap. Renegotiating social justice for the young. Opladen & Farmington Hills: Barbara Budrich Publishers, S.233–252

Grundmann, M., Hornei, I. & Steinhoff, A. (2013). Capabilities in sozialen Kontexten. Erfahrungsbasierte Analysen von Handlungsbefähigung und Verwirklichungschancen im menschlichen Entwicklungsprozess. In: Graf, G., Kapferer, E. & Sedmak, C. (Hrsg.), Der Capability Approach und seine Anwendung. Fähigkeiten von Kindern und Jugendlichen erkennen und fördern. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, S.125-148

Gasper, D. (2002). Is Sen’s Capability Approach an Adequate Basis for Considering Human Development? In: Review of Political Economy, 14 (4), S.435-461

Robeyns, I. (2005). The Capability Approach: a theoretical survey. In: Journal of Human Development, 6 (1), S.93-117

Robeyns, I. (2005). Selecting Capabilities for Quality of Life Measurement. In: Social Indicators Research, 74, S.191 - 215

Critical infrastructures

Critical infrastructures (CRITIS) are organizations and facilities that are indispensable for maintaining public safety and order as well as for keeping utilities running. Organizations and facilities in the energy-, information- technology and telecommunications-, transportation and traffic-, health-, media and culture-, water-, food-, finance and insurance-, municipal waste disposal-, and government and administration-sectors are part of the critical infrastructure in Germany according to Section 2 (10) BSIG (BSI Act). For these facilities, the IT Security Act 2.0 stipulates a need for increased security requirements.

References:

BBK–Bundesamt für Bevölkerungsschutz und Katastrophenhilfe. (2020). 10 Jahre „KRITIS Strategie “. Einblicke in die Umsetzung der Nationalen Strategie zum Schutz Kritischer Infrastrukturen.

Digital sovereignty

Digital sovereignty is the ability of individuals and institutions to perform their roles in the digital world independently, securely and self-determined (Goldacker, 2017, S.3). The term can be applied at different levels, like states, organizations or individuals. An EU parliament briefing defines Europe’s digital sovereignty as Europe's ability to act independently in the digital world, both in terms of protective mechanisms and offensive tools to foster digital innovation (including in cooperation with non-EU countries) (Tambiana, 2020, S. 1). Applied to individuals it centers around ensuring of user-autonomy and protection through providing user-friendly, transparent and safe digital technologies. Applied to states and businesses it includes the ability to the autonomy and safety of infrastructures, economic autonomy and competitiveness (Pohle & Thiel, 2021, S.8-12).

References:

Goldacker (2017).KOMPETENZZENTRUM ÖFFENTLICHE INFORMATIONSTECHNOLOGIE. Retrieved from https://www.oeffentliche-it.de/documents/10181/14412/Digitale+Souver%C3%... accessed on 24.03.2023

Tambiama, M. (2020). Digital sovereignty for Europe Digital sovereignty : State of play.European Parliament.retrieved from accessed on 24.03.2023

Pohle, J. & Thiel, T. (2020). Digital sovereignty. Internet Policy Review, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1532, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4081180

Digitization

The term digitization deals with the use of information technology (IT). In this context, the English-language literature distinguishes between three related terms, two of which are translated as "Digitalisierung" in German (Mergel et al., 2019; Wessel et al., 2021):

- Digitization: Digitization is the purely technical 1:1 translation from analog to digital. For example, existing analog forms are converted into digital forms without any structural changes.

- Digitalization: Digitalization adds an organizational level to digitization, i.e., in addition to technical changes, process improvements are also made. For example, processes are adapted so that digital forms request less data than analog forms did before, depending on the context.

- Digital transformation: Digital transformation is the adaptation of existing business models and the development of new value propositions using digital technologies. It extends digitalization to include not only the modification and improvement of existing processes, products and services, but also the development of new ones. For example, new public services are created that did not exist before.

References:

Mergel I., Edelmann N. and Haug N. (2019) Defining digital transformation: Results from expert interviews. Government Information Quarterly 36(4).

Wessel L., Baiyere A., Ologeanu-Taddei R., et al. (2021) Unpacking the difference between digital transformation and IT-enabled organizational transformation. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 22(1): 102–129.

E-Competencies

Competencies are the work-related knowledge, skills and abilities of an individual. In this context, the concept of competence is a broad capture of what an individual can achieve based on, for example, her/his education and experience. E-government competencies(e-competencies) are therefore those competencies that relate to the performance of public administration tasks in the context of the digitization of the public sector and go beyond individual skills or abilities.

E-competencies are divided into technical, socio-technical, organizational, managerial, and political-administrative competencies. At the same time, we assume that the requirements for and weighting of e-competencies also result from city-specific parameters, e.g., the type and number of administrative tasks, the number and structure of inhabitants, the city's function in the region, or the local economic infrastructure. Examples of e-competencies are IT competence, information system design competence, process management competence, e-policy competence and change management competence.

References:

Distel, B., Ogonek, N., Becker, J. (2019). eGovernment Competences Revisited – A Literature Review on Necessary Competences in a Digitalized Public Sector. In: Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik. Siegen, S.286–300

Hunnius, S., Paulowitsch, B., Schuppan, T. (2015). Does E-Government education meet competency requirements? An analysis of the German university system from international perspective. In: Proceedings of the 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, S. 2116–2123

E-Government

E-Government - the digitization of the public sector - is the use of information systems (IS) by public sector organizations (Lenk, 2002; Lindgren et al., 2021). E-Government encompasses both the provision of digital public services and the transformation to digital government itself (Lindgren & van Veenstra, 2018). The goal of this digital transformation is to make public administration processes more efficient (internal perspective) and thus to improve the delivery of public services to citizens and businesses as a whole (external perspective) (Yildiz, 2007). The digitization of services for citizens and companies on the one hand and of internal administrative processes on the other is therefore also referred to as the internal and external perspectives on e-government (Evans & Yen, 2006). The digitization of the public sector is largely influenced by the general (legal, social, economic and political) environment, the digital infrastructure, and policies and strategies (Lindgren et al., 2021)..

References:

Lenk, K. (2002). Electronic Service Delivery – A driver of public sector modernisation. Information Polity, 7(2,3), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.3233/ip-2002-0009.

Lindgren, I., Melin, U., & Sæbø, Ø. (2021). What is e-government? Introducing a work system framework for understanding e-government. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 48(1), 503–522.

Lindgren, I., & van Veenstra, A. F. (2018). Digital government transformation. Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research: Governance in the Data Age, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1145/3209281.3209302.

Yildiz, M. (2007). E-government research: Reviewing the literature, limitations, and ways forward. Government Information Quarterly, 24(3), 646–665.

Chou, T. C., Chen, J. R., & Pu, C. K. (2008). Exploring the collective actions of public servants in e-government development. Decision Support Systems, 45(2), 251–265.

Educational infrastructures

The concept of educational infrastructures refers to a stipulative rather than a lexical or theoretical definition. Educational infrastructures represent the entirety of all basics necessary for integral education. They encompass the entire spectrum (formal, non-formal, and informal) of educational and occupational biographies - from pre-school education, through primary, secondary, and higher education, to lifelong learning in the quaternary sector. Considering the requirements of all actors involved across the different levels, as well as the influences, that condition and construct accessibility to education, educational infrastructures can be thematized in four dimensions: material-structural, institutional-organizational, normative-cultural, and interactive-cooperative.

The material-structural dimension includes basics in the form of finances, buildings, material equipment, staffing, and the work of the administration. The institutional-organizational dimension takes a look at formal/non-formal and in-school/out-of-school educational institutions, institutions of the welfare state, and organizational structures. The normative-cultural dimension of educational infrastructures includes legal foundations as well as the influence of social and political discourses on education and its accessibility. The interactive-cooperative dimension of education focuses on the interactions and cooperations between actors in the multi-level system of education.

In terms of socio-ecological research heuristics, the concept of educational infrastructures aims at sharpening the view on the interaction of the different dimensions that condition, construct, and can mutually influence education and its accessibility, and thus to be able to grasp education holistically. The concept of educational infrastructures represents a bridging concept that integrates existing concepts on the topic of integral education, reveals possible needs, and offers guidance for empirical work.

Execution level

The executive branch implements the legislation specified by the legislative branch.

The level of execution indicates the level of the hierarchy (federal, state, local) at which the executing authority is located. At the execution level, the service defined by a legal norm specified at the regulatory level is provided. The executing authority provides resources to carry out the activities required to provide the service. The executing authority coordinates with partners, if necessary, to perform a task resulting from a law.

For this purpose, the executing authority interprets the scope for action given by the regulatory level into operational measures and, if necessary, expands the specifications with additional data, activities or the like. As a matter of principle, the executing authority is equal to or subordinate to the regulating authority in the level. Depending on the distance between the levels, additional requirements and room for maneuver can be specified by other higher-level authorities.

The executing authority can be supported in the course of administrative assistance by an authority that is not involved.

References:

Bundesministerium des Inneren und für Heimat 2021 OZG-Leitfaden: 6.2 Recht und Vollzug. https://leitfaden.ozg-umsetzung.de/display/OZG/6.2+Recht+und+Vollzug. Accessed 17 Mai 2023.

Bundesministerium des Inneren und für Heimat 2023 Verwaltungsvorschriften im Internet. https://www.verwaltungsvorschriften-im-internet.de/. Accessed 31 Mai 2023.

Europäische Kommission 2023 Anwendung des EU-Rechts. https://commission.europa.eu/law/application-eu-law/role-member-states-and-commission_de. Accessed 25 Mai 2023.

Bundesministerium für Justiz 2023 Art 35 GG - Einzelnorm. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/gg/art_35.html. Accessed 25 Mai 2023.

Hybridity / Blendedness

In the context of digitization, hybridity is the combination and mixture of digital and analog channels. In the field of midtown digitization, it focuses in particular on the blending of online and offline communication channels at the process level (Chadwick 2009). In this context, the use of synchronous, i.e., simultaneously / parallel used, digital and analog processes is defined as hybrid use (e.g., parallel face-to-face meeting and simultaneous online conference). Blendedness, on the other hand, describes asynchronous procedures that sequence various digital and analog procedures differently in time (analog stakeholder workshop, digital surveys, analog minipublic, digital open forum) (Kersting 2019).

Hybridity and blendedness do not describe a simple opening of both channels, but are often a purposeful, meaningful combination of analog and digital channels that lead to new forms of participation (blended participation) or education (blended learning). Administrative control and administrative processes often draw on analog and digital processes. The degree of hybridity describes the ratio between digital only and analog only.

References:

Chadwick, A. (2007). Digital Network Repertoires and Organizational Hybridity, Political Communication, 24:3, 283-301, DOI: 10.1080/10584600701471666

Kersting, N. (2019). Online Partizipation. Evaluation und Entwicklung- Status Quo und Zukunft. In: Hofmann, Jeanette et al. (eds) 2019: Politik in der digitalen Gesellschaft: Zentrale Problemfelder und Forschungsperspektiven. Bielefeld: Transcript: 105-122.

Intermunicipality; intermunicipal cooperation

In intermunicipal cooperation in the narrow/formal sense, two or more municipalities work together to provide a public service. Here, municipalities are usually driven by factors such as demographic change (shortage of skilled workers), dwindling financial resources or digitization. Through voluntary cooperation, municipalities can effectively counter the growing competitive pressure and increasing demands for action. However, this is not only triggered by (economic) necessity, but also by the pragmatic finding that joint work makes municipalities more effective and enables them to maintain or even increase the quality or quantity of their services.

Intermunicipal cooperation is based on the principle of voluntariness and is subject to the organizational sovereignty of the municipalities. Its form and content can be freely agreed upon, but it requires a corresponding law to regulate the cooperation in order to be able to provide the services in a legally binding manner. In this context,

- a new legal entity under public law can be created,

- a task can be transferred by breaking through the rules of competence (delegation),

- or a task can be carried out entirely on behalf of and according to the instructions of another municipality (mandate).

For these cases - for example - the Municipal Code of North Rhine-Westphalia and the Law on Municipal Joint Cooperation provide the following possibilities for cooperation between municipalities:

- municipal joint ventures,

- joint municipal enterprises,

- special-purpose associations or

- agreements under public law.

In addition to formal inter-municipal cooperation, non-public cooperation between municipalities will also play an important role in the context of the research group (intermunicipality). In particular, cross-municipal cooperation, e.g., between (sports) clubs and other organizations, should be considered here. This takes place in a private-law or informal framework.

References:

DStGB Dokumentation Nr. 39 (2004). https://www.dstgb.de/publikationen/dokumentationen/dokumentationen-nr-1-50/nr-39-interkommunale-zusammenarbeit/doku39.pdf?cid=6nj

DStGB Dokumentation Nr. 51 (2005). https://www.dstgb.de/publikationen/dokumentationen/nr-51-interkommunale-zusammenarbeit-praxisbeispiele-rechtsformen-und-anwendung-des-vergaberechts/doku51.pdf?cid=6m8

https://www.mhkbd.nrw/themenportal/interkommunale-zusammenarbeit

Intrinsic logic of cities ("Eigenlogik")

The concept of "Eigenlogik" was significantly shaped by the urban sociologist Martina Löw (2008) and her team. It is to be understood as an analytical scheme with which local structures and implicit constitutions of meaning of a city or cities can be made visible. From a social constructivist perspective, cities' own logics are also to be understood as patterns of experience that affect the people living in them. The inherent logic of a city, however, is not to be equated with city marketing or the public staging of cities. Rather, it is the result of negotiation processes and social references of urban actors. It manifests itself, among other things, in processes of homogenization and differentiation as well as in specific peculiarities of regionalization and the formalization of everyday and administrative routines. They all contribute to the (re-)production of the cities' sense of identity - especially in comparison to other cities.

References:

Löw, Martina (2008). Soziologie der Städte, Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Lifelong learning

Lifelong learning encompasses learning activity for people of all ages (children, youth, adults, and the elderly), in all spheres of life (family, school, community, workplace, etc.), and through a variety of modalities (formal, non-formal) that together cover a wide range of learning needs and requirements.

- Learning to know - The first pillar describes gaining awareness about a phenomenon and developing understanding and knowledge about it. Simultaneously, an individual learns to assess expectations toward that phenomenon and develops a need to learn more and more

- Learning to do - The second pillar describes the ability to act and especially to act appropriately in certain situations. Additionally, this is about the ability to pass on knowledge.

- Learning to be - The third pillar describes gaining awareness of one's own person and making the most of individual abilities and development opportunities.

- Learning to live together - The fourth pillar describes getting to know each other. Part of this is sharing experiences in societies, learning and growing as a group, and cultivating solidarity and support.

References:

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning Technical Note – Lifelong Learning. https://uil.unesco.org/fileadmin/keydocuments/LifelongLearning/en/UNESCOTechNotesLLL.pdf

Itzkovich, Yariv, and Niva Dolev. (2021). "Cultivating a Safer Organizational Climate in the Public Sector: Mistreatment Intervention Using the Four Pillars of Lifelong Learning." Societies 11.2, S.48.

Liveability

A city is said to be liveable if it is "safe, attractive, socially cohesive and inclusive, and environmentally sustainable" (Lowe et al., 2013). In this sense, liveability refers to the attractiveness of a place and its environmental conditions for living, working, and doing business (Rosemann et al., 2021; Tan et al., 2014; The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2019). Liveability is not based on perceptions alone, but also on objective criteria. Contributions to different dimensions of liveability by social actors, digitization measures or technological artifacts can therefore be measured concretely.

References:

Lowe, M., Whitzman, C., Badland, H., Davern, M., Hes, D., Aye, L., Butterworth, I., & Giles-Corti, W. (2013). Liveable, Healthy, Sustainable: What are the Key Indicators for Melbourne neighbourhoods?

Rosemann, M., Becker, J., & Chasin, F. (2021). City 5.0. Business & Information Systems Engineering (BISE), 63(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-020-00674-9

Tan, K. G., Thye, W. W., & Aw, G. (2014). A New Approach to Measuring the Liveability of Cities: the Global Liveable Cities Index. World Review of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, 11(2), 176–196.

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2019). The Global Liveability Index 2019. In The Economist.

Living lab

A living lab is a transdisciplinary research format that promotes collaboration between science and practice in order to develop solutions to societal problems. Living labs can also be described as testing spaces in which innovative technologies, regulations or concepts are tested and further developed under real conditions. In this way, the foundations for legal regulation can be developed in the experimental spaces, which are limited in time and space (BMWK 2019).

The research format of the living lab is based on three circular research phases of co-design, co-production and co-evaluation, which are developed cooperatively and participatively between science, practitioners, civil society and users. This can be done, for example, through group discussions, visioning workshops, experiments, questionnaires or interviews (Mbah et al. 2023).

Over the past 15 years, numerous approaches have been developed, ranging between transformative, technical-regulatory, and international living lab approaches. Living labs are mostly locally limited, but can also be regionally, nationally or transnationally oriented. Many projects are designed to last 2-5 years (Schäpke et al. 2017).

References:

BMWK – Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie (2019). Freiräume für Innovationen. Das Handbuch für Reallabore, Berlin online: https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Digitale-Welt/handbuch-fuer-reallabore.html [Zugriff: 25.04.2023].

Mbah, Melanie; Brohmann, Bettina; Weber, Manuela (2023). Das Reallabor-Format in der transdisziplinären Forschung. Vielfalt der Reallabor-Ansätze und ausgewählte ReallaborForschung am Öko-Institut, Workshopdokumentation Online: https://td-academy.org/tdacademy/themenlinien/themenlinie-4-neue-formate/kurzbericht-das-reallabor-format-in-der-transdisziplinaeren-forschung/ [Zugriff: 25.04.2023].

Schäpke, Niko; Stelzer, Franziska; Bergmann, Matthias; Singer-Brodowski, Mandy; Wanner, Matthias; Caniglia, Guido; Lang, Daniel (2017). Reallabore im Kontext transformativer Forschung. Ansatzpunkte zur Konzeption und Einbettung in den internationalen Forschungsstand, (No. 1/2017) Leuphana Universität Lüneburg, Institut für Ethik und Transdisziplinäre Nachhaltigkeitsforschung.

Medium-sized city

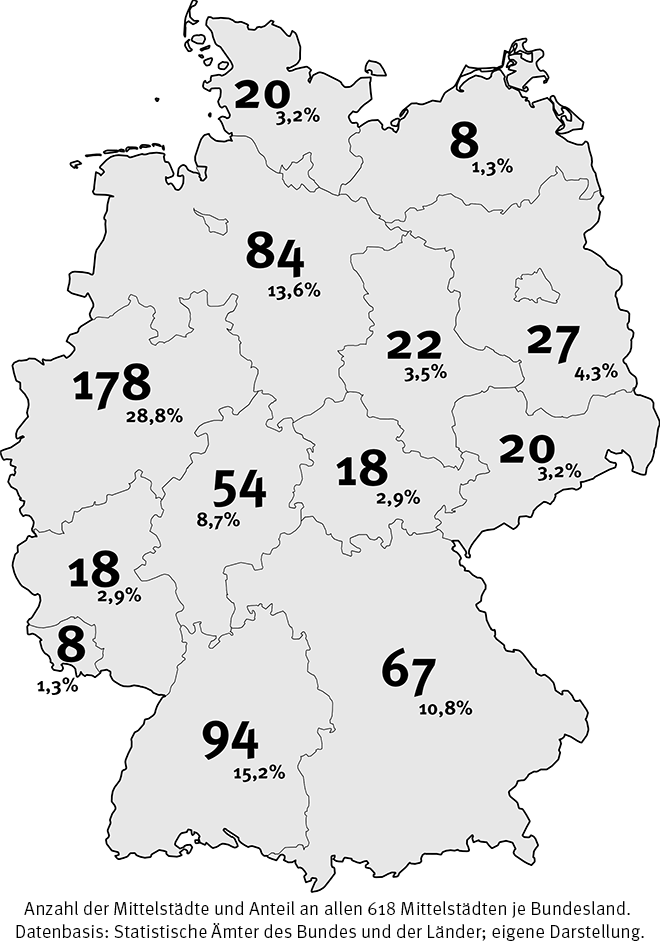

Following the definition of the International Statistical Conference of 1887, on which German municipal statistics are still based today, cities with 20,000 to 100,000 inhabitants are referred to as medium-sized cities (Adam, 2005). Accordingly, as of December 31, 2021, 5.7% of German municipalities are medium-sized cities (N=618). A total of just under 22.9 million people live in them. This corresponds to a share of 27.5% of the total population (own calculations, data basis: Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder 2023).

Medium-sized cities are particularly important socially, politically and economically in rural areas, where they perform central functions for surrounding smaller communities. At the same time, issues such as mobility, demographic change, economic development and a comprehensive range of educational opportunities pose challenges that are particularly relevant to medium-sized cities. In addition, for their (digitally supported) solutions, ressources are usually less available than in large cities (Becker et al., 2021).

Our research group analyzes challenges and and opportunities and develops tools so that digital medium-sized cities can develop, that preserve the identity of and identification with the city and region.

References:

Adam, B. (2005). Mittelstädte — Eine stadtregionale Positionsbestimmung. IzR - Informationen zur Raumentwicklung 2005(8): 495–523.

Becker, J., Distel, B., Grundmann, M., Hupperich, T., Kersting, N., Löschel, A., Parreira do Amaral, M., & Scholta, H. (2021). Challenges and Potentials of Digitalisation for Small and Mid-sized Towns: Proposition of a Transdisciplinary Research Agenda. Working Papers, European Research Center for Information Systems, 36.

Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder. (2023). https://www.regionalstatistik.de/genesis//online?operation=table&code=12...

One-Stop-Shop / No-Stop-Shop

One-stop-shop and no-stop-shop refer to two concepts for service delivery in public administration.

A one-stop-shop is the single point of contact for citizens and businesses to interact with different public administrations (Wimmer, 2002). All interaction with public administrations is done through this point of contact and there is no need to consult different contacts. While the front-end is integrated and centralized, the back-end can remain fragmented. Thus, case handling remains with the relevant authorities.

In a no-stop-shop, citizens and businesses do not need a point of contact to interact with the administration, as they do not need to do anything to obtain a pubilc service (Brüggemeier, 2010; Scholta et al., 2019). The administration does not request any data from citizens and businesses, but obtains it from other sources, and their consent to provide the service is not necessary either. Citizens and businesses only have to receive the service and can use it.

References:

Brüggemeier M. (2010) Auf dem Weg zur No-Stop-Verwaltung. Verwaltung & Management 16(2): 93–101.

Scholta H., Mertens W., Kowalkiewicz M., et al. (2019) From one-stop shop to no-stop shop: An e-government stage model. Government Information Quarterly 36(1): 11–26.

Wimmer M.A. (2002) A European perspective towards online one-stop government: the eGOV project. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 1(1): 92–103.

Participation

Participation generally refers to the participation in or possibility of influencing decision-making and will-forming processes as well as their implementation by individuals or organizations.

Political participation includes all activities that citizens "undertake voluntarily with the aim of influencing decisions at the various levels of the political system" (Kaase, 1992). Political participation is distinguished from civic engagement, which also includes social and public welfare participation.

According to Kersting (2013), political participation can be divided into four spheres, which, depending on the degree to which they are institutionalized, can be classified as "invited space" (top-down participation procedures organized by institutions) or "invented space" (bottom-up procedures initiated by citizens). Representative participation (1) is the most institutionalized form and includes, above all, participation in elections, involvement in political parties and the assumption of political office. Direct democratic participation (2) is also election-centered, but is oriented toward issues rather than persons, parties or offices (referendums, petitions, etc.). Deliberative participation (3) includes dialogue-oriented procedures (minipublics, participatory budgeting, etc.), which in Germany are mostly consultative and rarely oriented toward concrete decision-making. Finally, demonstrative participation (4) includes, for example, participation in demonstrations or writing letters to the editor. Digital forms of participation (e-participation) can be assigned to all analog participation areas. Examples include online elections (1), e-petitions (2), online participatory budgeting (3) or expressing political opinions in social media (4). In addition, we now often find processes that combine analog and digital instruments (blended/hybrid participation).

References:

Kaase, M. (1992). Politische Beteiligung/ Politische Partizipation. In U. Andersen & W. Woyke (Hrsg.), Handwörterbuch des politischen Systems der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, S.429-433 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-95896-9_103

Kersting, N. (2013). Online participation: From „invited“ to „invented“ spaces. International Journal of Electronic Governance, 6(4), S.270–280. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEG.2013.060650

Regulatory level

The legislative branch provides legislation for execution at the executive branch.

The level of regulation indicates the level of the hierarchy (federal, state, local) at which the unit responsible for defining the service resulting from a legal norm is located. This usually means that federal laws are defined at the federal level, state laws at the state level, and so on. The execution is performed by the execution level.

The regulatory level thus provides the execution level with room for maneuver and definitions of terms that are necessary for the provision of the service. Likewise, the regulatory level defines the necessary data that may or must be collected and processed in the execution.

In addition, there is an indirect execution, in which a regulatory level defines a law or service that is specified by a higher authority (e.g., EU law).

The executing authority can be supported in the course of administrative assistance by a non-involved authority.

References:

Bundesministerium des Inneren und für Heimat 2021 OZG-Leitfaden: 6.2 Recht und Vollzug. https://leitfaden.ozg-umsetzung.de/display/OZG/6.2+Recht+und+Vollzug. Accessed 17 Mai 2023.

Europäische Kommission 2023 Anwendung des EU-Rechts. https://commission.europa.eu/law/application-eu-law/role-member-states-a.... Accessed 25 Mai 2023.

Bundesministerium für Justiz 2023 Art 35 GG - Einzelnorm. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/gg/art_35.html. Accessed 25 Mai 2023.

Research Group "Future Digital Towns"

A research group is a medium-term, close collaboration of several outstanding scientists working on a special research task. The German Research Foundation (DFG) funds research groups; the funding period is usually eight years. The goal of a research group is to achieve results that clearly exceed the sum of the results of individual projects. The research group "Future Digital Towns" explores how medium-sized cities meet the challenges of digitization and develops digital tools to strengthen their liveability, taking into account the necessary capabilities in the areas of civil society & social services, administration & politics, economy & energy, and education & culture. The project involves researchers from the fields of business informatics, computer science, education, political science, sociology and economics.

References:

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (2022a). Forschungsgruppen. https://www.dfg.de/foerderung/programme/koordinierte_programme/forschung...

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (2022b). FOR 5393: Die digitale Mittelstadt der Zukunft. https://gepris.dfg.de/gepris/projekt/462287308

Security Automation, Orchestration and Response (SOAR)

Security Automation, Orchestration, and Response (SOAR) refers to IT systems that automatically collect IT security incidents, enrich them with cyber threat intelligence from various sources, and process them for IT security managers for the purpose of assessment and prioritization for the implementation of adequate measures. Since the analysis of these incidents is automated by SOAR systems and orchestrated with standardized processes ("workflows"), this leads to a significant reduction in response times and thus to increased resilience against vulnerabilities. Furthermore, SOAR systems can be programmed to automate processes that are traditionally handled manually and by multiple departments. An example of this is the creation of user accounts for new employees in an organization, who are to be given different rights and access to IT resources depending on their function and area of responsibility (account and identity management).

References:

Schlette, D. (2021). Cyber Threat Intelligence. In: Jajodia, S., Samarati, P., Yung, M. (eds) Encyclopedia of Cryptography, Security and Privacy. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-27739-9_1716-1

Further reading

López Velásquez, J. M., Martínez Monterrubio, S. M., Sánchez Crespo, L. E., & Garcia Rosado, D. (2023). Systematic review of SIEM technology: SIEM-SC birth. International Journal of Information

Services of general interest ("Daseinsvorsorge")

Services of general interest are the provision of services or goods that are necessary for the public. This includes "energy and water supply, transport services, telecommunications, broadcasting, street cleaning, and sewage and waste disposal" (Chardon, 2021). In addition to supply infrastructure, services of general interest also include cultural, social and charitable services (Deutscher Bundestag, 2006, p.2). It emerges constitutionally from the welfare state principle. The municipal ordinances of the federal states define the services included in more detail. How these are implemented, however, is largely left to the municipalities themselves. Services of general interest can therefore be provided both by the municipalities themselves and, for example, by private service providers. At the same time, services of general interest are a political concept whose scope and legal relevance are the subject of public debate. (Deutscher Bundestag, 2006, S.2f).

References

Chardon, M. (2021, October 6). Daseinsvorsorge. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Retrieved from https://www.bpb.de/kurz-knapp/lexika/das-europalexikon/176770/daseinsvor..., accessed on 24.03.2023

Deutscher Bundestag. (2006). Was ist Daseinsvorsorge? Historische Entwicklung, aktueller Stand, Aufgaben der Kommunen, Bedeutung des Begriffs in der aktuellen Debatte. retrieved from https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/424316/40836520741496c15613a91f11..., accessed on 24.03.2023

Spatial Justice

The spatial justice approach, developed by scholars such as Soja, Harvey and Lefebvre, provides a perspective on justice and links justice to space. According to Soja's (2010) spatial justice approach, social and spatial processes interact with each other and and shape the structure of justice.

In the literature two strands of perspectives on spatial justice can be differentiated: The distributive approach focuses on the material quality of space. Here, the distribution of resources, goods, and access in space and the interactions that exist here are considered in particular (Schwab, 2018). The procedural approach focuses more on the processes of decision-making and adopting measures as well as their fairness (Schwab, 2018).

Space does not necessarily have to be interpreted geographically, but can be understood as a dynamic set of relationships. We can think of digital, formal, or informal spaces as well (Schwab, 2018). The approach supports being able to observe and point out divisions in medium-sized cities and to identify influencing factors (Beach et al., 2018; Oberti & Prétéceille, 2016).

References:

Beach, D., From, T., Johansson, M. & Öhrn, E. (2018). Educational and spatial justice in rural and urban areas in three Nordic countries: a meta-ethnographic analysis. Education Inquiry, 9(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2018.1430423

Oberti, M, Prétéceille, E. (2016). La ségrégation urbaine. [Urban segregation] Paris: La Découverte.

Schwab, E. (2018). Spatial Justice and Informal Settlements: Integral Urban Projects in the Comunas of Medellín. https://doi.org/10.1108/9781787147676

Soja, E. W. (2010). Seeking Spatial Justice. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816666676.001.0001

Sustainable urban development

Sustainable urban development is to be understood as an urban development policy model that develops the vision of a transformed city in the sense of sustainable development, which is based on the equivalence of ecological, economic and social sustainability, as well as on inter- and intragenerational concepts of justice (Görgen/Wendt 2015).

In 2007, in the context of the EU Council Presidency, Germany developed the Leipzig Charter, which drafts the version of a European sustainable city and an integrated urban development policy and focuses on the networking of numerous actors and the strengthening of disadvantaged neighborhoods. On the occasion of the EU Council Presidency 2021, a new Leipzig Charter was developed, which focuses on the transformative power of cities and the promotion of the common good in terms of the three pillars of sustainability (Leipzig Charter 2021). In addition to an integrated urban development approach, this charter focuses on the participation and co-production of numerous actors, especially from civil society, as well as a multi-level and place-based approach to meet the key challenges of sustainable urban development and socio-political challenges. This concept combines approaches of cooperative urban development, with sustainability, citizen participation, locality under the perspective of the common good and thus addresses no less than the central issues of the 21st century (WBGU 2016; SynVer*Z 2021).

References:

Görgen, B., & Wendt, B. (2015). Nachhaltigkeit als Fortschritt denken: Grundrisse einer soziologisch fundierten Nachhaltigkeitsforschung. Soziologie Und Nachhaltigkeit, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.17879/sun-2015-1443.

SynVer*Z - Synthese- und Vernetzungsprojekt Zukunftsstadt (2021). Wie leben wir morgen. Forschungsimpulse für eine nachhaltige Stadt, Berlin: Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik.

WBGU – Wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesregierung für globale Umweltfragen (2016). Der Umzug der Menschheit. Die transformative Kraft der Städte, WBGU: Berlin.

Transdisciplinarity

Transdisciplinarity refers to research approaches that aim to address scientific research questions in a differentiated and integral way, in particular by linking different types and forms of knowledge and involving different groups and actors in the field. Furthermore, the mutual learning between the involved scientists and practitioners about the complex, socially relevant process of digitalization in different fields is central (Max-Neef, 2005; Rigolot, 2020; Scholz & Steiner, 2015). It represents a promising way of knowledge production and decision-making (Lang et al., 2012).

Research in a transdisciplinary framework is characterized by four key features:

- integration of knowledge from different disciplines;

- integration of different types and forms of knowledge (disciplinary knowledge and practice/stakeholder knowledge);

- inclusion of relational and rational approaches of explanation and understanding;

- triangulation of research approaches.

On the one hand, transdisciplinary work promotes the understanding of the complexity of correlations as well as the attainment of a lifeworld perspective on the objects of research. Knowledge-oriented research on the one hand and design-oriented research on the other hand support each other and an innovative symbiosis emerges.

References:

Lang, D. J., Wiek, A., Bergmann, M., Stauffacher, M., Martens, P., Moll, P., et al. (2012). Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Science, 7(1), 25–43.

Max-Neef, M. A. (2005). Foundations of transdisciplinarity. Ecological Economics, 53(1), 5–16, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800905000273.

Rigolot, C. (2020). Transdisciplinarity as a discipline and a way of being: complementarities and creative tensions. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 100.

Scholz, R. W., Steiner, G. (2015). Transdisciplinarity at the crossroads. Sustainability Science, 10(4), 521–526.